The work of museum staff is not solely focused on presenting objects for public display. There is a lot that goes on in the offices and laboratories of museums that the average person never gets to see. One big initiative that is going on in many museums is to use technology to make their collections more accessible – so even if you can’t go to the museum itself you can hear the stories their collections have to tell.

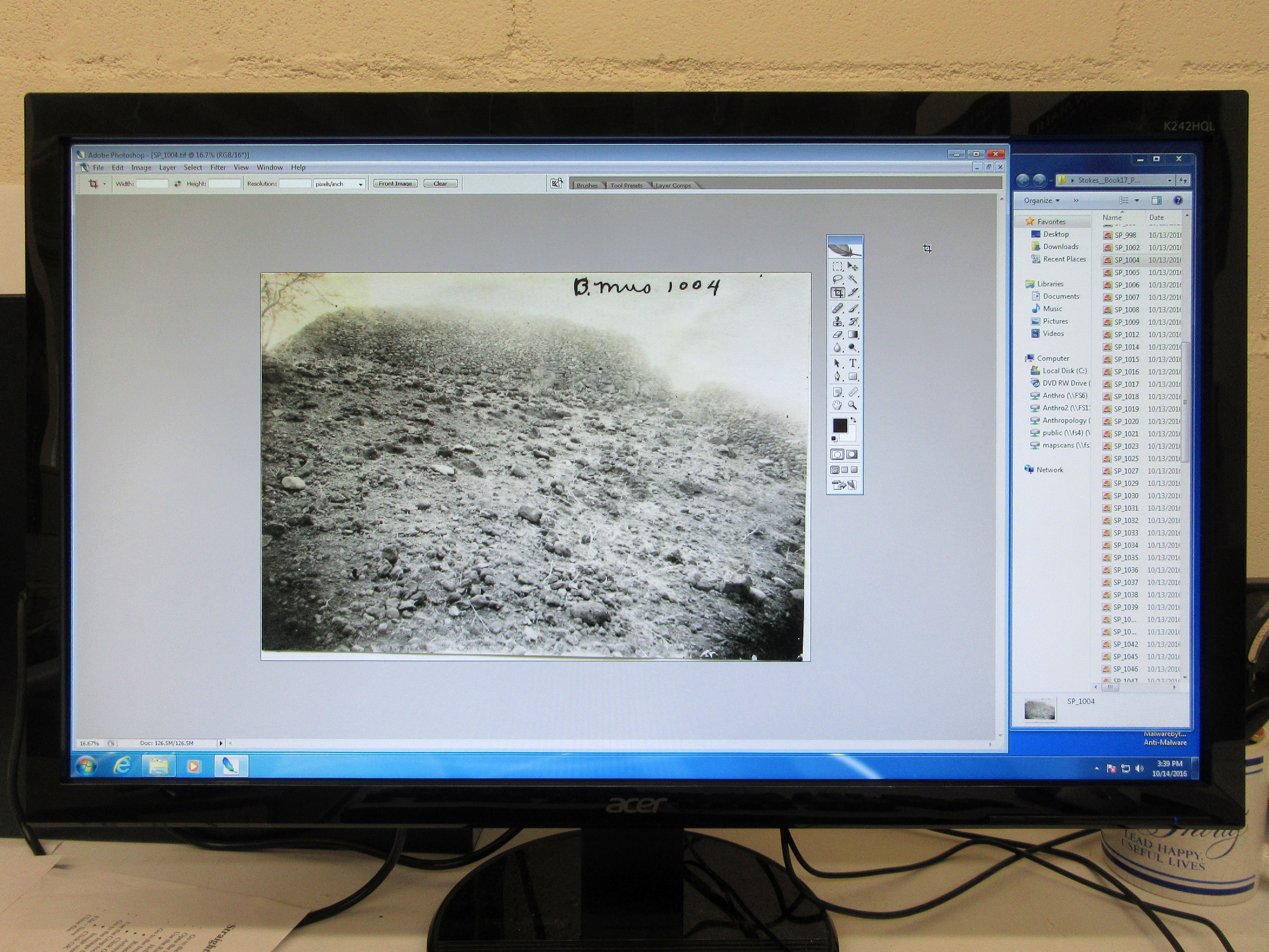

Many people don’t realise that an important component of museum collections is their paper archive. A museum’s archaeology collection may contain survey maps, personal communications, photographs and excavation notebooks. All of these materials are very important historical resources and can be very delicate. By digitising them the need for handling is reduced and they can be studied without exposing them to potential damage. One of my tasks at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu was to scan and crop archival photos from the Stokes Collection. Together with William Brigham, the first director of the Bishop Museum, John F. G. Stokes was part of the first major archaeological survey of Hawaiian heiau in 1906-1909. These photos of archaeological sites, people and places are a record of Hawaii long before the tourists and resorts arrived. Some of these collections will soon be available through a new online database and through them we can see the Hawaii that Brigham and Stokes were exploring over 100 years ago.

Museums also often receive private collections donated by individuals or their families. In many cases there is a lot of work to be done before these donations can be integrated into the existing collection. If the donor is still alive, the museum’s collections manager can ask them for the information needed about where the objects/documents came from, when they were acquired and how they have been stored and used. It is really important to not allow objects that could be infected with something like woodworm to be exposed to the priceless objects already in the collections, so there is a long process that goes on first to ensure the new objects are safe. Even books have to go through this: boxes of books were stored in a big chest freezer while I was at the Bishop Museum to kill any potential pests to ensure that no pests were inadvertently introduced to the Archaeology Lab or collections areas.

Material is sometimes donated to museums from archaeological researchers who are based in other parts of the world. If the museum is the major repository of material from that archaeological time period or geographical area then it may be the best place for these materials so that they can be accessed and studied by other researchers in the future. While I was at the Bishop Museum I helped to catalogue donated thin section slides of 3,000-year old Lapita pottery from the western Pacific that was studied by William Dickinson, who was one of the foremost experts in this area. These are thin slices of pottery sherds cut with a diamond saw and ground flat until they are microns thin and can be mounted on a glass slide. The slides can be examined under a powerful microscope to identify the minerals contained in the pottery which can tell archaeologists about the type of clay and inclusions used to form the pottery, which can then be used to track the movement of raw materials. Once completed, this catalogue will be accessible to interested researchers from all over the world.

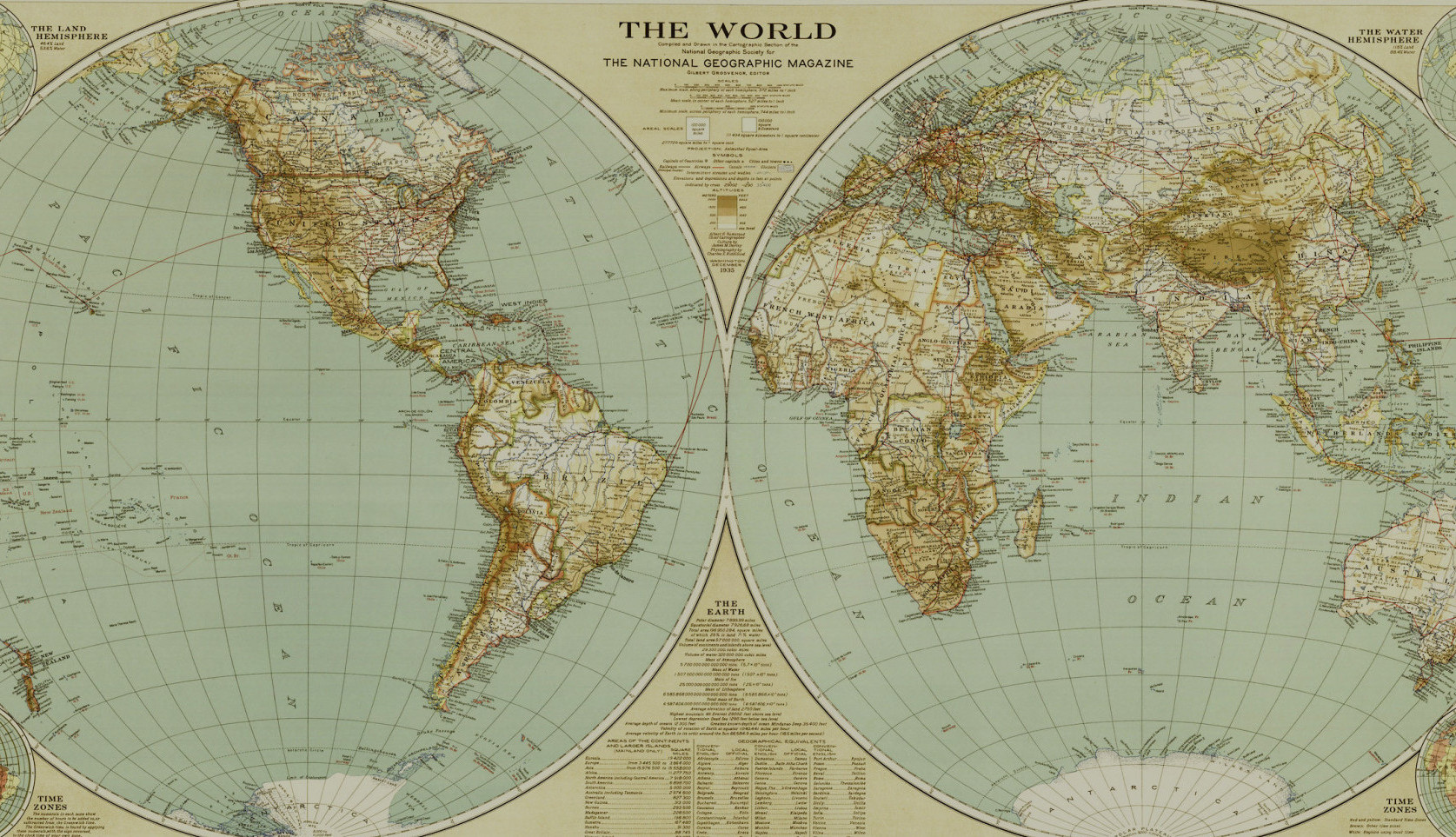

The creation of online databases so both researchers and the public can access and explore collections remotely is an important component of the work currently being done by the Bishop Museum. There is a continuously rotating squad of volunteers who work diligently to process and digitise the Archeological Collections of the Anthropology Department. Already this work had produced results: the Ho‘omaka Hou Research Initiative Online Fishhook Database, the Hawaiian Archaeological Survey (HAS) Database, and the Rapa Nui Interactive Radiocarbon Database can all be accessed online through the Bishop Museum website. The Hawaiian Archaeological Survey (HAS) Database is a searchable catalogue of over 12800 Hawaiian archaeological sites investigated by Bishop Museum archaeologists – a valuable resource for anyone interested in learning more about Hawaiian archaeology.

Going behind the scenes at a museum gives you an insight into how archaeological collections are stored and prepared for display in the museum’s galleries, but equally important is the work done to showcase these collections digitally. This is an area of museum work that could not have been imagined when the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum was opened in 1889!