An article from the Winter 2020 Issue of Popular Archaeology reproduced with the permission of the editor.

Naxos is the largest island in the Greek Cycladic group, located in the Aegean Sea between the Greek and Turkish mainlands. The islands’ varied landscapes combine to give it a special character. Known for its rich land and bountiful crops as well as for its beautiful white marble and abrasive emery, I could make a journey from a sandy beach to a leafy mountain village in about an hour. Wherever I looked my eye found archaeological treasure and history: from Classical temples to Byzantine architecture. It was also all around me as I made my way through the peaceful Naxian villages and towns. The winding medieval lanes of central Chora are perfect examples of places where one is completely immersed in a medieval town-scape with a view: from the top of the medieval Venetian kastro (castle) the Classical temple of Apollo can be seen across the harbor. However, less known to the world, recent archaeological excavations on Naxos have revealed a far older prehistoric legacy on this island.

Beginning in 2013, an international team led by Dr. Tristan Carter of McMaster University through the Canadian Institute in Greece, and his co-director Dr. Demetris Athanasoulis of the Cycladic Ephorate of Antiquities of the Hellenic Republic’s Ministry of Culture and Sports, has conducted a series of ongoing excavations at what is currently the earliest known archaeological site in the Cycladic region. Located on Stélida hill on a promontory that juts out into the Aegean Sea, archaeologists and student volunteers of the Stélida Naxos Archaeological Project (SNAP) have uncovered a wealth of lithic (stone) material suggesting that Stélida was a place used to acquire raw material to form stone tools as long ago as at least two hundred thousand years.

Digging Up an Ancient Quarry

In the summer of 2016 I spent a month with the SNAP team at Stélida as part of my Global Archaeology project. Standing at its summit, I could view the coastline and the sea spreading out before me toward the west. I could clearly see Naxos’s hilly neighboring island, Paros, across a short distance of water. The area is very dry, and the visual contrast between the dry yellow earth and vegetation and the vivid turquoise sea is striking. But what drew me to Stélida was not the view—it was the stone beneath my feet. Stélida was first identified as a significant source of chert in 1981 as part of a survey by the École Française d’Athènes under the direction of René Treuil. Chert is fine grained sedimentary rock that was commonly used in prehistory by hominins and anatomically modern humans for producing stone tools and weapons. SNAP excavation trenches are located on different parts of the hillside, with two archaeologists working at each trench. Every morning of the excavation season the team begins the daily climb from the bottom of the hill and ascends the 118 m hill to their designated trenches. The path is literally littered with lithics – stepping on archaeological material is impossible to avoid at Stélida. By spreading the team across a large area, many different aspects of the prehistoric activities once carried out there can be investigated simultaneously and a more informed picture of the use of this landscape can be developed. This has also allowed the team to refine their research focus over time and explore specific areas of the hillside that are producing particular diagnostic types of lithics — stone material modified by hominins or early humans that are telling us something about when they were made and their material culture.

In 2016, SNAP was focused on opening a few new excavation trenches at the very base of the hill and towards the summit, as well as revisiting some that had been opened the previous year. I was tasked with opening and excavating a new 2m x 2m trench about ¾ of the way up the hill, positioned immediately at the base of a substantial chert outcrop. Without contest this is the most artifact-rich site I have ever excavated. The downside of such a rich site is that what I was excavating was mostly stone – not an easy material through which to shovel. We quickly developed a working rhythm with the passing of time, marked by the ferries sailing past us through the channel between our island, Naxos, and neighboring Paros. It seemed to be a contradistinction to be doing hard labor at a location surrounded by holiday villas and resorts where vacationers were being pampered. Our reward: only the archaeologists were afforded a view of the beautiful sunrise over the Aegean every morning from the top of Stélida hill.

__________________________

Stélida as viewed from the north on Naxos. D. Depnering

__________________________

View from Stélida toward the sea. Kate Leonard

__________________________

The 2016 excavation trench. Kate Leonard

__________________________

Stone tools and other lithics in situ at Stélida. Kate Leonard

__________________________

New Data, New Insights

More recently, the SNAP team has focused on evidence from a particular excavation trench — DG-A/001 — laid out toward the summit on the western side of the hill on a debris cone at the base of a chert outcrop. The 2 m by 2 m excavation trench was dug to a depth of 3.8 m through stratified colluvial deposits — translated, this means the excavators dug twice the height of a tall man through sediment and stone that had both originated at that specific location and washed down the slope from the summit over hundreds of thousands of years. This is tough work through mostly stone compressed in a matrix of soil – not the type of excavation that uses brushes to expose delicate surfaces. In the process, excavators revealed more buried prehistoric soil layers. Using infrared stimulated luminescence dating, a technique used to measure the time elapsed since the last exposure of soil samples to sunlight, levels were dated from 13.8-12.1 thousand years ago toward the top of the trench to 219.9-189.3 thousand years ago toward the bottom of the trench. From this trench, approximately 12,000 artifacts were excavated and over 9,000 of those were in strata (layers or levels) dated to the Pleistocene. The diagnostic lithics (stone objects indicative of particular time periods and/or cultural groups) found in DG-A/001 included Upper Palaeolithic tools — usually associated with modern humans, or Homo sapiens — Middle Palaeolithic technologies (such as Mousterian — usually associated with Neanderthals ), and examples of Mediterranean tool-making traditions from the early Middle to Lower Palaeolithic. Middle and Lower Paleolithic activity at Stélida was also evident in 159 diagnostic artifacts previously identified during surface surveys on the hillside.

The calcareous soil at Stélida was not conducive to the preservation of organic materials and so the excavators worked down through layer upon layer of mostly stone flakes, cores and debitage. When I dug with SNAP, for more than a meter below the modern ground surface the material I was excavating was over half composed of lithic debitage. In terms of volume of artifacts vs. non-artifacts, Stélida is by far the most artifact-rich site I have ever excavated. Like many prehistoric and historic quarry sites the artifacts that were uncovered at Stélida represent the early stages in the production of stone tools and as such the excavation team did not uncover many easily identified stone tools like those that would be found on a habitation site. The majority of what they uncovered was the material evidence of stone extraction and reduction activities. The team was digging through the evidence of quarrying (extraction) and the initial formation of pieces like rough cores (reduction). From the type of lithic material that was found in the excavations at Stélida it can thus be assumed that the higher quality pieces of chert were selected and taken elsewhere by the ancient toolmakers for final processing and use.

While much of the lithics excavated from Stélida are not easily discernible artifact types and analysis is often done of material from the early stages of the reduction process, there have nonetheless been some diagnostically identifiable types excavated from well-sealed and dated contexts. Some of the lithics from Stélida are consistent in their form and modification with artifacts from other well-dated Mesolithic and Lower to Upper Palaeolithic sites in Greece and Anatolia. There is also known Middle Palaeolithic activity at Stélida identified from diagnostic prepared core technology. This means that some of the anthropogenic (human-modified) material found here can be securely dated to the time when Neanderthals were living in Europe. But what the newly published evidence from Stélida tells us is that it is possible there were other hominid species quarrying and using Stélida chert even earlier. For instance, there is potential evidence for Lower Palaeolithic activity at Stélida in the form of possible bifaces that could be interpreted as handaxes. It is plausible that these large heavy tools could have been made by Homo heidelbergensis, the predecessor of the Neanderthals in Europe. The possibility for evidence of these early hominids living on what are now the Cycladic Islands has not been seriously investigated before—until now.

Activity Patterns and Behavior

As an archaeologist, I was interested in knowing if the SNAP team had come across any patterns in the evidence they were revealing. Were similar types of artifacts found in the different trenches? Or do the artifacts suggest different periods of use in different areas of the Stélida hillside? As I corresponded with Carter, he told me that “for the most part we [the SNAP project team] seem to be finding a lot of similar stuff across the site” but noted, however, that “there are some greater concentrations of certain periods”. So the team has identified that generally, similar types of lithic material are found across the hillside, with some concentrations demonstrating more intensive use at certain locations during certain periods. For instance, surface surveys have uncovered more Middle and Lower Palaeolithic material from the areas toward the summit of the hill in front of two identified rock shelters and in the vicinity of the coast at the bottom of the hill, than in other areas. From the evidence uncovered in the excavation trenches the Mesolithic is best represented by the materials uncovered at the top of the Stélida hill, Upper Palaeolithic material is found “everywhere”, and Middle Palaeolithic evidence found below the summit and in the middle of the hill’s slope (although intermixed with later material). Interestingly, the loose concentration of excavated Middle Palaeolithic material comes from an area associated with both a rock shelter and an ancient spring.

Carter revealed another fascinating observation. “The work of my colleague Dr. Dora Moutsiou suggests that there are hints of raw material preferences through time.”—With this statement, he suggests that the evidence from Stélida may show that particular types of chert may have been preferred by different hominins at different times. Middle Palaeolithic materials are more often the slightly grainy grey and orange cherts sourced from around Stélida’s Rock Shelter A (basically an area of collapsed rocks upslope from a spring) and further north on the hill, while the Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic materials are more often made of the lustrous white-blue chert sourced from the southern summit of Stélida. The suggestion therefore is that when they visited Stélida to quarry, Neanderthals were looking for grainy grey-orange chert and, later, Homo sapiens were looking for smooth white-blue chert. Perhaps this was part of the prehistoric oral history of Stélida – passing down through generations not only what the landscape was like and how to get there, but what sort of stone tool making materials would be found once they arrived.

The assemblage excavated by SNAP from Stélida is comprised exclusively of lithics due to the highly alkaline nature of the hills’ calcareous soil. The only location so far excavated by SNAP that may produce information about any organic presence on the hillside in the prehistoric period comes from a trench located in front of Rock Shelter B. But Carter clarified for me that “we are not permitted at present to excavate inside the two shelters […] as that falls under jurisdiction of a different bureau of the Greek Ministry of Culture”. The trench just outside of Rock Shelter B contained traces of in situ hearths that may be of Upper Palaeolithic date. According to Carter the fauna from this context is microscopic and is being investigated by a specialist in sedimentary aDNA analysis (a technique to identify evidence of animals and plants via extracted traces of aDNA from soil samples) at the McMaster University ancient DNA laboratory. It is hoped that this innovative technique will expose another facet of what the environment was like at Stélida in the Palaeolithic. Tantalizingly, Carter stated that some of the plant remains from the potential hearths “might be material for matting [or] fuel”. There will be more to come on this once the data is published.

__________________________

Aerial view of Trench DG-A/001 (or ‘Trench 1’). Evaggelos Tzoumenekas

__________________________

Team member Irina Kajtez (Belgrade University) excavating Trench 1 (DG-A/001) in 2015. Rachit Srivastava

__________________________

Shannon Crewson (McMaster University undergraduate in 2015) documenting the excavation of Trench 3 (DG-A/003) in 2015. Rachit Srivastava

__________________________

Ioanna Aslamatzidi (undergraduate Athens University) and Hanna Erftenbeck (PhD candidate Note Dame University) screen for finds on Stelida, 2017. Jason Lau

__________________________

Justin Holcomb (co-author and PhD candidate Boston University) takes and prepares a soil sample from the lower levels of DG-A/001 (‘Trench 1’) for micromorphological studies to understand the development of the deep archaeological sequence. Jason Lau

__________________________

Geological hand sample of Stelida chert. Nikos Skarpelis

__________________________

Beatrice Fletcher (PhD candidate McMaster University) studies a stone tool from the excavations, 2015. Rachit Srivastava

__________________________

Implications: A Shifting Paradigm

When the Stélida area was first reached by hominins the landscape would have been much different than what we see today. Scientific investigations into the ancient environment suggest that the modern islands of Naxos and Paros were joined with others as part of one great island known as the ‘Cycladean Island’ during the glacial maximum (the stage of the Ice Age when the maximum amount of sea water was trapped in glaciers). Paleogeographic reconstructions of the area indicate that during the interglacial periods of the Quarternary (the time period from 2.59 million years ago to the present), sea levels may have been low enough to expose a land bridge between the Greek and Anatolian peninsulas that would have resembled a wetland environment rich in resources. One can envision that tens of thousands of years ago when hominins and anatomically modern humans climbed the hill at Stélida to reach the chert outcrops they would have been looking out over a green, grassy plain, an estuary or even a lagoon, with the sea many kilometers away. It is likely that they were not only attracted to the great Cycladean Island for the Naxian emery, chert at Stélida, or the basalt and obsidian of the nearby island of Melos, but equally for the hunting and foraging opportunities provided by the surrounding wetland environment.

The average person with an average lifespan would find it difficult to fathom a time span of 1 million years. This is the amount of time that has passed since hominins first moved into Europe from Africa, during the Lower Palaeolithic and before anatomically modern humans had even evolved. There is no current way to know if Stélida or somewhere else in the vicinity was a location used for long-term habitation during the Palaeolithic. Due to the nature of the site and the material record available for dating, precise dates for the exploitation events at the chert source are not possible. It is unclear whether the use of the site in the Lower to Middle Paleolithic was intermittent, opportunistic or consistent. Nevertheless, the archaeological material being uncovered suggests that Stélida was a place hominins and anatomically modern humans came back to again and again to extract chert. The question remains: how did they get there?

Early Mariners?

It has always been assumed that these early hominin explorers of Europe were not able to make boats (even the most basic) and so could never have traversed large bodies of water like seas. However, the current evidence from the Palaeolithic environment models tell us that there would not have been large bodies of water to cross in the region of Naxos. At worst, the crossings would have been much smaller, with hominins likely seeing the next landfall within sight of their point of origin. Tides would still have had an effect and at different periods in prehistory the depth and width of the water being crossed would have varied depending on the total glaciation. If water crossing was necessary (as opposed to land bridges) the craft fashioned by the early quarriers may not have resembled what we think of as boats today, but clearly they were effective in allowing Stélida to be accessed again and again for hundreds of thousands of years. The results from SNAP can therefore be described as ground-breaking evidence for alternative route-ways for Homo sapiens and their ancient predecessors’ movements from Asia into Europe.

With this, the possibility of pre-sapiens accessing locations like Stélida triggers a new understanding of what these hominins may have been capable of cognitively. This includes the capacity to communicate complex ideas through shared language, perhaps the construction of vessels to carry them across bodies of water, an understanding of the moon and tides, likely the ability to identify landmarks and return to a site previously visited and/or to follow directions passed on from another, and the ability to navigate a landscape and environment quite different from those elsewhere in Eurasia. To support such a fundamental shift in our understanding of pre-sapien hominin capabilities, a robust data set and sample size that can be scientifically dated from a clearly stratified excavation, like Stélida, is required.

The SNAP excavations and analysis has revealed the first stratified, large, and well-dated Pleistocene lithic assemblage from the Cyclades that allows for the assertion that hominin and anatomically modern human dispersals into Europe traversed through areas, like the Aegean Basin, that have been previously viewed as inaccessible. The team suggests that instead of a single route into Europe from the Anatolian peninsula it is more likely that pre-sapiens and anatomically modern humans took a variety of routes for a variety of reasons. Until now there has been no robust evidence for Middle Pleistocene cultural activity in the central Aegean; Neanderthals and earlier hominins were thought to have been present only on either side of the region, continental Greece and the Anatolian peninsula. Now, new evidence suggests that the Aegean Basin region was open for consistent use by hominins throughout the Palaeolithic.

_____________________________

Location of Stélida archaeological site and hypothesized hominin dispersal routes: 1, Stelida; 2, Rodafnidia; 3, Karaburun; and 4, Plakias. Base map modified from Lykousis 2009 (22). Figure by J.H.

_____________________________

Reconstruction of prehistoric spearheads hypothesized to have been made from stone material at Stélida – of Lower, Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, plus Mesolithic date (L-R). Kathryn Killackey

_____________________________

Select artifacts from Stélida. Flakes unless otherwise noted. a, scraper; b, backed flake; c, bladelet; d, piercer; e, piercer on blade-like flake; f, piercer; g, combined tool (burin and scraper on chunk); h, nosed scraper; i, combined tool (inverse scraper/denticulate/notch); j, denticulate (LU5); k, flake; l, denticulated blade-like flake (LU7); m, piercer; n, denticulate; o, denticulate; p, piercer; q, combined tool (linear retouch/denticulate); r, scraper; s, convergent denticulate (Tayac point); t, blade; u, scraper; v, denticulate; w, linear retouch; x, tranchet; and y, blade-like flake (LU6). Photographed by J. Lau and modified and page set by N. Thompson.

_____________________________

Moving Forward

The SNAP team will be returning to Stélida for another season of excavation in 2020, with continued support from the Canadian Institute in Greece for a new five-year research permit from the Greek Ministry of Culture. Carter plans to return to some very deep (4.5 m) trenches that were opened in previous seasons to obtain further dates, and to start some new excavation trenches in areas of the hillside that may contain less disturbed deposits. The positioning of the new trenches is based on a detailed topographic analysis, says Carter: “We used drone photography to produce a 5 cm resolution digital elevation model and using that with GIS to reconstruct micro-watersheds, and interrogate artifact distribution”. Further work will also be done at the summit of Stélida, but Carter is currently tight-lipped about additional new discoveries the team has been making there — a clue that Stélida will continue to reveal new boundary-pushing evidence of early hominin and anatomically modern human activity in the Aegean.

Read the latest report on the Stélida excavations in Science Advances.

___________________________

SNAP team photo 2019, with young scholars and students from Canada, Greece, England, France, Serbia and the US. Valerie Seferis

___________________________By Kate Leonard

Kate is an archaeologist and adventurer who is passionate about sharing her love of archaeology with the world. Her doctoral research focused on the Irish Late Bronze Age but her fieldwork has no borders! Over her career Kate has surveyed, excavated, and worked in museum collections on four continents. In 2016 she set off on a self-directed project, Global Archaeology, where she participated in 12 projects in 12 countries in 12 months. While lending an experienced helping hand to exciting archaeological projects she explored the world and documented the journey through social media (www.globalarchaeology.ca). For Kate, archaeology is fascinating because it reveals stories of our shared global past, but equally as important is the way these stories can connect people in the present. Now Kate has settled back in her home country of Canada where she is continuing to do archaeological writing while spending her days exploring the Rocky Mountains.

]]>Peru has been a country I’ve been interested in visiting for a long time. The images of Inca temples, women dressed in brightly coloured woven textiles, baby llamas and forest covered mountains didn’t prepare me for the diversity of the modern country I arrived in. One goal of the trip was to visit Machu Picchu and reach it by a route that would let me experience Peru away from an urban centre. The variety of landscapes traversed on the Salkantay Trek really appealed to me, but I hadn’t anticipated coming across some heritage gems along the way.

Day 1 started in the city of Cusco with a 4 am pick up followed by a four hour drive to a breakfast stop. We then went to the start of the trek at Challacancha, 3350 meters / 10990 feet above sea level. We were one of many small groups each with one guide who got us organised and led us up a narrow track into the countryside. Only a few short minutes into the hike we were walking alongside a narrow, masonry sided aqueduct that I assumed to be modern as the water was flowing through it very well and some repairs could be seen. The aqueducts were actually built during the Inca period and continue to supply water to farmers today. Water management in the arid Andes was a key mechanism for the expansion of Inca rule and was also closely tied to spirituality in the mountains.

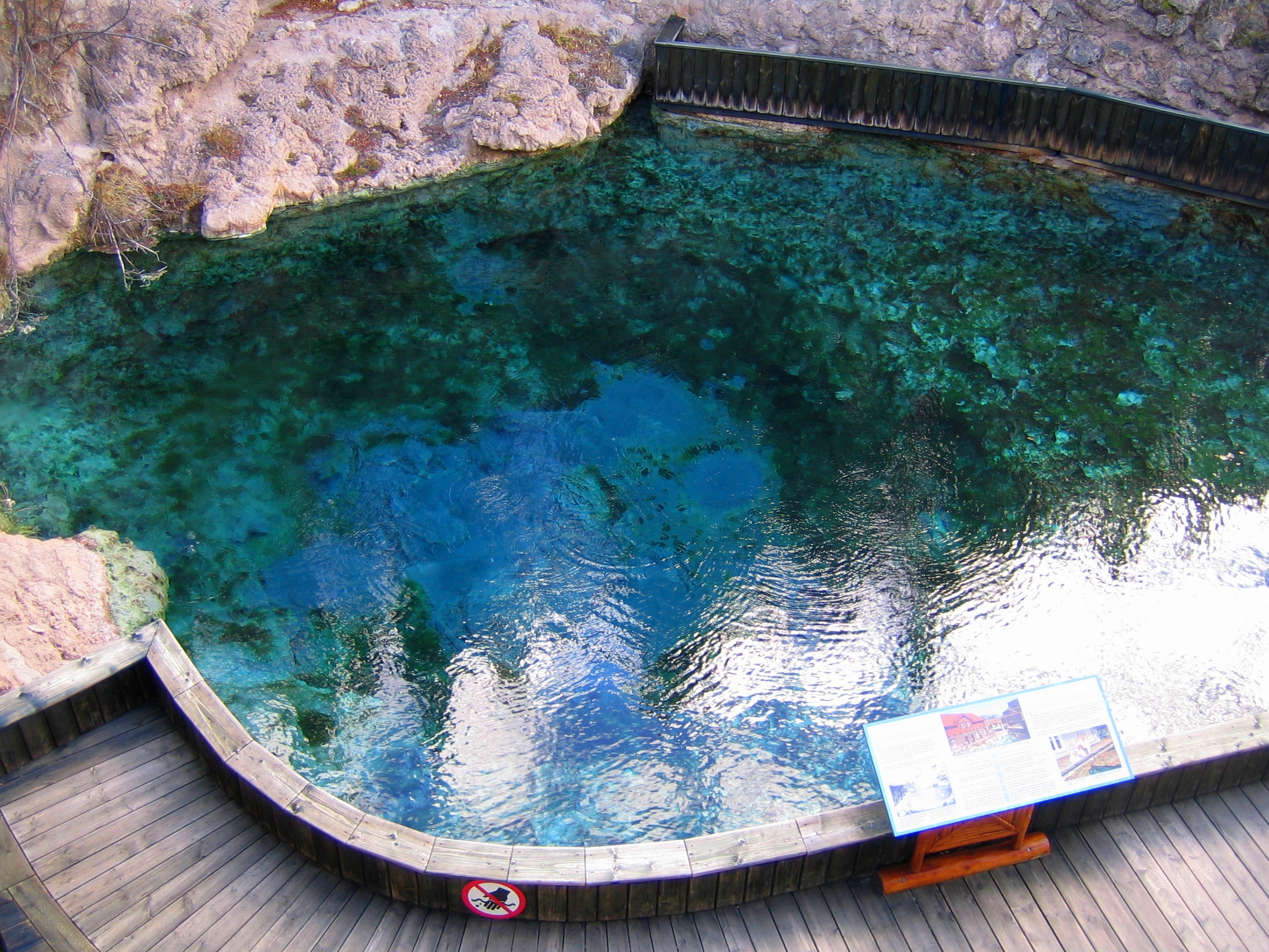

Continuing onwards and upwards we reached our camp at Soraypampa, 3920 meters / 12861 feet above sea level, where we had a short rest and lunch. In the afternoon we proceeded further upwards to the beautiful Humantay Lake at 4200 meters / 13779 feet above sea level, framed by the mountain glaciers of Apu Humantay. All around the lake Peruvian and international travellers have left tokens and offerings to the mountain gods. We did the same before heading back down to camp. Through our glass roof we could see the moon rise over the snow-capped mountains and I knew we were off to a good start.

Day 2 started with a quick breakfast at 5am (early starts were becoming a trend….) followed by a trek up through the mists. On the way we passed a group of feral llamas that were considerably more wild than those we had seen posing for tourist photos in Cusco. By mid-morning we were in the centre of the Andes mountain range climbing through the Salkantay Pass, 4650 meters / 15255 feet above sea level, surrounded by the towering peaks of the Salkantay, Humantay, Tucarhuay and Pumasillo mountains. Our guide sat us down for a moment and explained that Salkantay Mountain is the second highest mountain in the region and one of the Inca gods. I had mixed feelings coming through the other side of the pass and moving into the Amazon cloud forest – the mountains had left a strong impression on me.

Day 3 was another early start, but we had already begun our descent and so it was at least considerably warmer at 2750 meters / 9022 feet above sea level. Over the day we walked on narrow paths perched on the sides of steep hillsides, often with a turbulent river far below us. After the open alpine landscape of the previous days the lush forest seemed busy and full of colour! Along the way we stopped at a farm to try some fresh passion fruit and avocados. It was a delight to come around a bend in the path and see an orchard of passion fruit through the forest. Another stop was at an organic coffee plantation where we learned about historic roasting methods and sampled some of the local brew. Today coffee is the main farming industry in this part of the cloud forest, coffee having become popular after the Spanish invaded Cusco in the 16th century.

Day 4 was a warm, humid start, which really made it feel like we had travelled far from the cool, dry air of Cusco. For me, although the elevation was much lower at 2450 meters / 8038 feet above sea level, the heat of the day made the trekking much more challenging. As we walked the sun climbed further and the tropical forest began steaming (and I probably was as well). The earth seemed bursting with vegetation and everywhere we could see flowers and hear water moving in drops, streams and waterfalls. At one point a flock of green parrots flew in complex formations through the valley beside use, filling the air with noise. This portion of the day was an ascent along a section of the Inca Trail with tantalising glimpses of Huayna Picchu and Machu Picchu mountains hovering in the distance.

The highlight of this day was the Llactapata ruins which is positioned directly across a vast steep mountain valley from the site of Machu Picchu. A Royal Geographical Society supported team led by Hugh Thomson and Gary Ziegler investigated Llactapata in 2003 and uncovered a central plaza with doorways that are aligned with Machu Picchu as well as a two-storey temple which faces the rising sun. When mapped it was seen that Llactapata is composed of as many as five sectors and covers several square kilometers. The investigators propose that Llactapata was a constructed in relation to Machu Picchu and perhaps as a place to take astronomical readings. Our guide suggested Llactapata was a site for preparation prior to a sacred journey to Machu Picchu. In particular he noted a sunken channel that runs through a chamber through a doorway aligned with Machu Picchu and linked it to the sacred nature of water in the Andes. Regardless of its original purpose, the site is striking and was a wonderful quiet counterbalance to its more famous counterpart.

From Llactapata we had an afternoon of descent through the forest and then along the train tracks and Urubamba River towards the town of Aguas Calientes, 2000 meters / 6561 feet above sea level. Along the way we had some fantastic views of the Machu Picchu site far above us – a reminder of the climb we would be doing the next day. This was the last leg of our trek before meeting the goal of seeing Machu Picchu and it really had been a fantastic way to make the journey to such an iconic archaeological site.

Indigenous belief is that Cusco sits at the navel of the world. It certainly felt like we had traveled into the centre of Peru as we journeyed through the Andes to reach the city. Situated in the Huatanay river valley, Cusco is surrounded on all sides by mountains and many of its districts are accessed by steep steps. As the gateway city to many Andean treks (including Machu Picchu – more on that in a later post) Cusco is an ideal place to acclimatise to the altitude of the mountains. At 3400 m (11 200 ft) above sea level, I could definitely feel the increase in elevation from the coast.

Cusco is the official Historical Capital of Peru and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage City in 1983 for exhibiting and representing 3000 years of pre-Inca occupation, the establishment of the Inca Empire in the 13th – 16th centuries AD and the colonisation of Peru by the Spanish in the 16th century AD. This history can be physically seen and touched as you walk through the streets in the Centro Histórico. Cusco was redesigned in a monumental style while under the rule of Inca Pachacuteq (Tito Cusi Inca Yupanqui) in the 15th century and the Spanish literally built on top of what was there: European baroque and renaissance architecture sitting on colossal Inca foundations. This is very evident in the Convent of Santo Domingo which was built on top of the most important Inca structure in the city, the Qurikancha (Sun Temple). The interior has recently undergone restoration and the Inca foundations and some of the original temple walls can now be explored. When you view the Qurikancha from the park outside the juxtaposition of the Inca and Spanish architectures is striking.

The historic centre of Cusco is heaving with tourists and those trying to sell things to tourists. To orient ourselves amongst all this activity we joined a walking tour that gave us an overview of the architecture, history and culture of the city. We started at the Plaza de Armas de Cusco, known as the “Square of the Warrior” by the Incas and today as the touristic heart of the Centro Historico. The square is bordered by grand colonial entrance gates and arcades that house shops, restaurants and cafes, some with upper level balconies that are great spots for people watching. On one side of the Plaza de Armas stands La Catedral, begun in 1560 AD and finished 100 years later. The Renaissance style La Catedral was built on top of the palace of the eighth Inca ruler, Viracocha, from stones taken from the nearby pre-Inca archaeological complex, Sacsayhuaman. Around the corner, on the foundations of the Amarucancha (the palace of Inca ruler Wayna Qhapag) stands the equally impressive 15th century baroque style Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús.

The Calle Loretto is an interesting lane just off of the Plaza de Armas where you can see Inca foundations for structures secondary to the sacred temples and palaces. The stones are smaller than those used to build the elite structures and of slightly rougher, but clearly highly skilled, masonry. Walking down this lane gives you an idea of what the city must have been like under Inca rule. Around the corner is the Kusicancha, the birthplace of one of the most important Inca rulers, Pachacútec, and now an archaeological site that is also home of the offices of the Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INC). The archaeological excavations revealed the foundations of an Inca cancha – city block – without the later Spanish architecture obscuring it. You can enter the site and walk freely among the foundations and view some of the artefacts that were uncovered during the excavations. This is a lovely spot to step away from the crowds as it is very peaceful and not often visited.

Also off of the Plaza de Armas is Calle Hatunrumiyoc the street where you can find the famous Twelve Angled Stone. Originally part of the wall of an Inca palace, the giant diorite stone is a wonderful example of Inca masonry. The street is quite narrow and the huge stones that make up the walls on either side seem to tower over you. Continuing down (or perhaps up) this street you pass into the Barrio de San Blas, a vibrant artisan neighbourhood. This is the place to find hand-woven textiles, alpaca products, religious artwork and a variety of other treasures. The steep narrow streets are just wide enough for a small car with steps on either side for pedestrians. It is an ideal spot to learn about traditional Peruvian arts and handicrafts from the artisans themselves. Entering a doorway to examine a keepsake that caught your eye, you often find yourself emerging into an open courtyard in the colonial style with arches surrounding the lower level and balconies above. From every wall and on every table there is colour and choice! It is hard to decide on just one thing to take home with you.

For a completely different experience the San Pedro Market is not to be missed. This huge covered market, similar to ones I’ve visited in Europe and Mexico, contains stands selling everything from freshly made juice to raw meat to alpaca sweaters. We were in Cusco in the days leading up to the Easter holiday so there was an amazing array of traditional pastries and goodies for sale. The aisles are tight, there are items spilling off shelves and every shopkeeper is trying to get your attention. While there are many stalls filled with items clearly geared towards tourists, this is definitely where Peruvians come to get a bowl of soup and fill their bags with groceries. Getting a bit outside of the historic centre of the city is worth it to see a side of Cusco that is not tourist oriented.

Cusco is a big city with many high profile monuments and hidden gems to explore. I felt that my time there exposed me to a facet of Peruvian culture and Peru’s past that I hadn’t seen in Lima or in the holiday focused areas along the coast. The stamp of the Inca Empire remains bold in Cusco, making each stroll through the streets feel like an expedition. I could have stayed longer, but like many other visitors, I had a trek to embark on: through the Salkantay Pass and on to Machu Picchu.

There are some sites that embody the concept of archaeology for me. I’ve been to a few (Acropolis of Athens, Chichen Itza) and still have some on my bucket list (Egyptian Pyramids, Stonehenge). This is the first in a series of four posts about my journey through Peru to one of these iconic sites: Machu Picchu.

We arrived into Lima at 12:45am local time. It seemed like a long time since leaving the Rockies. The airport and customs were easy enough to navigate and when we stepped out into arrivals there was a woman holding a sign with my name on it. I was still wearing my down jacket (I had left the end of Canadian winter) and the coastal air around me felt hot. We were bustling into the taxi by 1:30am and I could tell I was in for a wild drive through a sleeping city (I was correct).

Lima is huge. It is the capital of Peru and has a population of about 9 million people. I live in a town of 5 thousand so the pace and volume of such a large urban centre caused a bit of culture shock. We were staying in the Miraflores district (established by the Spanish in the 16th century) on the edge of the central plaza Parque Kennedy. The park is busy with foot traffic during the day and with an artisan and craft market in the evenings. To the south and also on the coast is the bohemian district of Barranco which has lovely colonial architecture, graffiti art and flocks of Black vultures. It was a nice spot to have a cold beverage and watch the sun set over the Pacific.

Perhaps against my better judgement, on our second day in Lima we took the city bus from Miraflores to the historic centre – the Cercado de Lima district. It was humid and the bus was crowded to sardine can proportions. But, we made it, the price was right, and I felt like I had accomplished something many tourists would not attempt. This UNESCO World Heritage Site is the oldest colonial district in Lima and within the old city walls contains the Presidential Palace (1535 AD), the Basílica y Convento de San Francisco (1674 AD) and the Cathedral Basilica of Lima (1535 – 1649 AD).

After exploring the busy historic centre, Parques de la Muralla was a welcome shady and quiet place for a picnic lunch. Underneath our picnic bench lay the remains of the old city wall which is restored and displayed as part of an outdoor museum. The final stop in the historic centre was the Barrio Chino. Lima’s China Town developed in the 1850’s during an influx of Chinese immigrants, many of whom came to Peru as contract labourers to work in the sugar plantations or for railway construction. The Barrio Chino grew around large Chinese commercial import companies which attracted smaller businesses, shops and temples to the district. Today the revamped area is marked by an archway gifted to the barrio in 1971 by the people of Taiwan. When you walk through it you are bombarded by the sights, sounds and smells of Chinese-Peruvian culture, best experienced by trying one of the Chifa restaurants.

I was keen to see more of Peru so we jumped on an early bus headed south to Paracas. On the way we stopped at Tambo Colorado, an Inca adobe complex in the Pisco River Valley. The site is amazingly well preserved, including the vivid yellow and red painted walls, and we were lucky enough to be the only ones who had stopped there to look around. The walled complex is roughly u-shaped and made up of a series of terraces and structures that surrounds on three sides a central plaza facing a sacred mountain. The most likely purpose for the 15th century AD site is that it was used as an administrative centre by the Inca elite to control the main route from the coast into the highlands. It is an incredibly well built and still impressive site.

The next day was another early start, this time to head out to sea. The Ballentas Islands National Reserve is a major tourist attraction just off the coast of Paracas which can easily be visited by tour boat. On the way to the islands you pass the 180m/595ft tall El Candelabro prehistoric geoglyph that is cut into the northern face of the Paracas Peninsula in Pisco Bay. The site has been dated to 200 BCE and likely was created by the Paracas culture before the arrival of the Inca culture to the area. Motoring around the islands you can see a variety of bird species like pelicans, booby’s, Humbolt penguins, and (when we visited) a sea lion nursery! From the sea we traveled straight into the desert landscape of the Paracas National Reserve where condors soared above the red sand.

Peru is certainly a country of diverse landscapes and next I found myself in an oasis resort in the middle of a sea of sand dunes. Huacachina is a natural oasis and tourist hotspot that is now known for dune buggies, sand boarding and sunsets. The legend of the lagoon is a classic one involving a beautiful maiden observed by a hunter while bathing and who dropped her mirror when she fled, thus creating the lagoon. In the 1940’s the oasis was developed as a spa retreat for wealthy Peruvians from Lima – and the village retains a crumbling vestige of this retro elegance. Not being one for dune buggying, I opted for sunbathing on the rooftop terrace, enjoying some Peruvian cuisine at a lagoon-side café and hiking up to the top of a sand dune to enjoy the sunset.

The next stage in the journey was a long one that involved an overnight bus through mountain passes. It started with a Pisco vineyard tour and tasting outside of the city of Ica where we learned about the fermentation process and how pisco differs from European style wines: sugar and time! We then continued further south until reaching the famous Nazca lines where we could see the Lizard, Tree and Hand. These huge geoglyphs are surprisingly shallow when seen up-close, they are only 10-15cm (4-6 inches) deep. The Nazca Lines were made between 500 BC and 500 AD by the Nazca culture who removed a layer of reddish-brown pebbles from the ground to reveal the yellow-grey soil beneath. It is this stark colour difference that makes the figures stand out so clearly.

It was incredible to see part of such a geographically huge (the Nazca lines as a group covers approximately 50 km2 / 19 miles2) and renowned archaeological site up close. I tried to keep this enthusiasm during the further 12 hour bus journey from the town of Nazca into the Andes Mountains. Next stop: the Inca heartland.

Head-Smashed-In-Buffalo Jump; Le Précipice À Bisons Head-Smashed-In; Itsipa’ksikkihkinihkootsiyao’pi’

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump was one of the first Canadian indigenous archaeological sites that I became aware of as a child. It was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1981 and the Interpretive Centre at the site was officially opened in 1987 by the Duke and Duchess of York (Prince Andrew and his then wife Sarah Ferguson). It must have been celebrated on CBC news and television in the late 80s and 90s and entered my subconscious then. It has always been on my archaeological bucket list and I finally made a visit this summer.

The sandstone cliffs of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump sit in rolling grassland at the edge of the Porcupine Hills, foothills of the Rocky Mountains in the territory of the Blackfoot people who have been on these lands for time immemorial. Unfortunately when I made my visit the air was full of smoke from the wildfires raging in southern British Columbia and north-western Montana and I could not see much of the surrounding landscape. There is an interpretive trail along the top of the cliff from which (on a clear day) you can see north to Calderwood Buffalo Jump and Vision Quest hill, east across the prairies, and south to the Rocky Mountains. My view of the more immediate area of the cliff and the surrounding grassland was shared with a few marmots and mule deer.

When you arrive at the Visitor’s Centre the helpful staff at the front desk suggest that you start at the very top of the building with the cliff-top interpretive trail and then make your way down through the exhibit areas to the cinema where you can watch a re-enactment of how the cliffs were used in the past for buffalo hunting. The exhibits start with descriptions of the surrounding landscape and the culture of the indigenous people who hunted buffalo in the past (the ancestors of the Blackfoot peoples who are still stewards of this land), the focus then moves to the process of ensuring a successful hunt through ritual and careful preparation. This was followed by highly organised co-operative work to move the animals through the landscape to the cliff and also to process the animals if the hunt was a success. The exhibits on the lower levels discuss how the practice of hunting buffalo in this way came to an end with the colonisation of the land and persecution of indigenous peoples by European settlers. In this area of the Interpretive Centre the archaeological excavations that have taken place are also explored.

The concept of driving a herd of buffalo over a cliff seems straightforward until you begin to read the interpretive panels in the Interpretive Centre (watch the Travel Alberta video here). Buffalo do not have strong eyesight but they do have a keen sense of smell – two things the indigenous hunters knew well and used to their advantage. When the herd was spotted in an area close to a jump site the ceremonies and preparations would begin – often days in advance of the actual hunt. A major part of the preparations was to rebuild and enhance the stone and brush cairns that created the drive lanes. The buffalo perceived these widely spaced cairns as solid walls and the hunters used them to move the herd towards the cliff. The edge of the cliff was hidden by a slight rise, so the drop could not be seen until it was too late. At the last moment the hunters would emerge from behind the cairns and cause the herd to stampede over the edge.

Before the hunt began the hunters would participate in ceremonies to prepare both people and buffalo. The hunters would cleanse in a sweat-lodge to ensure the buffalo would not identify them with their keen sense of smell – the hunt would only be conducted when the wind was blowing toward the cliff so the buffalo would not get spooked by human smells from behind them. Some hunters would dress as calves to entice the cow buffalo towards the cliff edge, others would dress as wolves to push the buffalo forward. The injured buffalo were killed at the base of the cliff and quartered and skinned before these more manageable sized pieces were dragged to the processing camp. If all went to plan the hunt could ensure a large group would be fed, clothed and equipped for months. The buffalo provided meat, fat, hides, bone, horn and sinew that was all processed into food (fresh and dried), clothing material, equipment and tools – nothing went to waste.

We know that the majority of hunts at Head-Smashed-In-Buffalo Jump took place in the fall because buffalo are all born at the same time of year and archaeologists have been able to age the bones found at the site. This was the first site in the province of Alberta to be excavated by a professional archaeologist (in 1938) and has been a focus of academic study since that time. The archaeological deposits at the base of the cliff represent over 5700 years of periodic use – the deposit is over 10 meters thick! It is a fascinating place to visit – allowing the visitor to physically experience the landscape where these hunts took place. It is not surprising that the UNESCO World Heritage Committee deemed it ‘a site of outstanding universal value forming part of the cultural heritage of mankind’. According to Parks Canada: “Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump is one of the oldest, most extensive, and best preserved sites that illustrate communal hunting techniques and the way of life of Plains people who, for more than five millennia, subsisted on the vast herds of bison that existed in North America”. I recommend you visit and see it for yourself.

It seemed that everywhere I turned in Québec City, the capital of the Canadian province of Québec, there was another National Historic Site. I couldn’t decide which to focus on first – so instead chose the whole area of Old Québec (Vieux-Québec), declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985. The historic district of Vieux-Québec is located on Cape Diamond (Cap Diamant), a promontory that overlooks the St. Lawrence River, a major thoroughfare from the Atlantic Ocean to the interior of Canada. This distinct quarter of the city includes the Upper Town (Haute-Ville) on the Cap Diamant promontory and the Lower Town (Basse-Ville) at the base of the cliff next to the St. Lawrence River. What began as a military fort above and fortified trading post and settlement below is today a Mecca for history buffs.

The Upper Town (Haute-Ville) is the former site of Fort Saint Louis, established by the French explorer Samuel de Champlain in 1608. The Upper Town is enclosed by the Ramparts of Québec, the only enduring fortifications walls in northern North America (north of Mexico). These walls were declared a National Historic Site of Canada in 1957. The four remaining gates into the fortified Upper Town include the Portes St. Jean, St. Louis, Prescott and Kent. The currently standing gates in the wall are all later rebuilds of those that originally allowed entrance into the city. Port St. Jean is technically the oldest, having been originally built in 1694, but its current manifestation is a 1939 rebuild of the 1791 and 1865 rebuilds. Today most of the buildings we see while walking through the streets of the Upper Town date to the 19th century, with a few from the 17th and 18th century dotted throughout.

One of the most recognisable structures within the Upper Town is the Château Frontenac. Designated a National Historic Site in 1980, this iconic railway hotel was constructed in 1892 and sits on the location of the Château Haldimand, the seat of the British colonial governors of Lower Canada and Québec from 1786-1866. The Château Frontenac was designed for the Canadian Pacific Railway company by the architect Bruce Price as one of a series of hotels. Newer portions of the hotel were designed by the architect William Sutherland Maxwell. On the river side of the Château is the wide wooden Dufferin Terrace and beneath its boards are the remains of the Saint-Louis Forts and Châteaux archaeological site (designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 2001). When the Dufferin Terrace needed maintenance work in 2005 there was an opportunity to conduct archaeological excavations of the remains of Fort Saint Louis and its’ châteaux. This was an extremely rewarding excavation – revealing extensive architectural remains spanning from the 1620’s to the 1800’s and about 500 000 artifacts. Today Parks Canada facilitates visitor access to the exposed archaeological remains.

After the British conquest in 1759 the Upper Town was occupied mainly by British government officials and Catholic clergy. This change in the governance of Québec was the result of one of the most pivotal battles in Canadian history: the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. In September 1759, General James Wolfe led British troops up the steep cliff of Cap Diamant to the plateau immediately west of the Citadelle of Québec (stay tuned for the next blog post to learn more about this fascinating National Historic Site of Canada). The British, armed with muskets, arrived under the cover of darkness and ambushed the French who were under the command of the Marquis de Montcalm – the battle likely lasted under half an hour. The French settlement of Québec thus came under British control, a significant point in the evolution of what is now Canada. In fact, The Plains of Abraham are so important to the Canadian story it became Canada’s first National Historic Site in 1908.

The Lower Town (Basse-Ville) was the site of a settlement of interconnected buildings known as the Habitation de Québec, also founded in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain. This fortified trading post was the first permanent French settlement in North America – marking the founding of the City of Québec and one of the first major European footholds in Canada. The location of this early settlement is now centred round the Place-Royale and the Catholic Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church, built between 1687 and 1723, and selected as a National Historic Site of Canada in 1988. During the Battle of the Plains of Abraham the church was heavily damaged and it took until 1816 for the restoration to be complete.

Sitting at a patio table in one of the many restaurants in the Basse-Ville you can examine the surrounding buildings at your leisure. The two and three story plastered stone homes are typical of the French architectural style of the 17th century with their dormer windows, large chimneys and party walls that rise above the gabled roofs to act as firewalls. Once the British began governing Québec City in the mid 1700’s the Basse-Ville was occupied mainly by French and English merchants and artisans. Today you can reach the Lower Town from the Upper Town by the series of steps culminating the Escalier Casse-Cou (Breakneck Stairs), or take the funicular car from the Rue Petit-Champlain up to the Terrace Dufferin and the Château Frontenac.

I entered Québec City via the historic railway station the Gare du Palais (Palace Station) and made the steep trek up the Cote du Palais to my accommodation. Built in 1915 by the Canadian Pacific Railway the château-esque station is located where the Charles River meets the mighty St. Lawrence River to the west of the Old Port (Vieux Port). Ships navigated the St. Lawrence River throughout the 1600’s and the export of Québec’s natural resources stimulated the construction of naval dockyards here in 1738. The Vieux Port is considered the oldest port in Canada and was also one of the world’s five most important ports in the 19th century – supplying (among other goods) huge Canadian timbers to Great Britain. In this period the port was also the gateway to Canada for Irish and British immigrants who were processed at the immigration shed at the Louise docks.

The few days I spent in Vieux-Québec were not nearly enough to fully experience and appreciate all this location has to offer. The number of significant historic locations within such a small urban area is unparalleled in Canada and so you really do feel like you are catching a glimpse of a bygone age as you walk down the narrow streets.

Sometimes you end up visiting sites you never thought you would – sites that are off of the beaten track. It might be that you see a road sign that grabs your attention and you make a detour, you happen upon a site when you are in an area for another purpose, or that a trip is arranged for you to a place you had never thought of visiting. Last autumn I was lucky enough to make such a trip to Fort St. James National Historic Site in the heart of the province of British Columbia.

Fort St. James NHS is on the edge of the small town of Fort Saint James where the southern shore of Stuart Lake meets the Stuart River. When Simon Fraser and John Stuart established the fort in 1806 for the North West Company the surrounding area was known as New Caledonia. The view over the lake from the fort is stunning and there are extensive forested hiking trails in the surrounding area to explore. From the site’s Visitor’s Centre you can walk through the wooden palisade wall and into the fort or you can walk outside the palisade along the lake’s edge. Once inside the walls there is a lot to do: investigate the historic objects on display in the buildings, listen to the costumed interpreters, see the baby goats and bunnies, or take your chances at the Chicken Races.

The site boasts the largest Canadian collection of restored original wooden buildings from the height of the fur trade. The Fish Cache and Fur Warehouse are particularly significant examples of 19th century buildings typical of the fur industry in the region. Also within the palisade walls are the Hide Tanning Shed, Dairy, Murray House, Men’s House, Trade Store and General Warehouse. Not to be overlooked is the Commemoration Café – where you are guaranteed a delicious lunch (I recommend the ribs – but have a small breakfast). The five historic buildings and other reconstructed building are under regular monitoring and maintenance to combat the effects of time and conserve them for future generations to enjoy.

In 1948 the fort was declared a National Historic Site – even though it was still in operation as a trading post until 1952! A large Hudson’s Bay Company flag flies above the site reminding you of the economic impetus that fueled its’ foundation and longevity. Restoration based on historical and archaeological research began in earnest in the 1970’s and presents the site as a snapshot in time of what it would have been like at the end of the 1800’s. The current Parks Canada Site Manager, Bob Grill, has been working at Fort St. James since 1975 and has literally helped to reconstruct the site to what we see today. When you visit you are surrounded by the physical record of the fur trade of the Pacific Slope of Canada – a historically significant centre of trade, transportation and cultural interaction.

Fort St. James exhibits the historic activities and objects of the fur traders as well as the Indigenous groups who have ties to the location and region. Indigenous partners provide advice on site management and Indigenous Interpreters interact with site visitors in the Hide Tanning Shed in the fort itself. In addition to touring the historic structures of the fort, visitors can explore the exhibits in the Visitor Centre to get more detailed information about the site and the historically significant people who have a page in the story of the region. If you are looking for a truly immersive experience you can stay in the officer’s dwelling (Murray House) or the Men’s House – among the historic artefacts and alone in the 19th century fort all night!

There was something very special about being able to stand at the edge of the palisade and look out over Stuart Lake to take in the same view the Hudson’s Bay Company trappers and traders. Walking through the site I imagined it as a gathering place – somewhere people returned to after long journeys and time spent in the wilderness. The fur trade was a major influence in pushing European explorers west across the continent along the network of lakes, rivers and mountain passes. The fort is an important reminder of this specific period in Canada’s development.

The rabbits, goats and chickens (did I mention the Chicken Races? Chicken Racing Video) definitely add to the site’s activities on offer, but they also remind us that those who established and used the fort had to be self sufficient. The historic inhabitants were a long way from any other centres of trade. If the town of Fort Saint James seems remote today it must have seemed ten times more so in 1896. I felt like a child when I was exploring the site – it was difficult to keep myself from running from building to building to see what treasures were inside each one. One visit certainly wasn’t enough for me!

If you are interested in learning more click on the links above and here for a Parks Canada video title The Metis of Fort St. James NHS.

On a warm day late last summer I went to explore Jasper House National Historic Site. The dry air smelled like a wood stove and the usually crisp Rocky Mountains that surround the town of Jasper were softened. We were in Jasper National Park in the province of Alberta, but the smoke from forest fires raging in the neighbouring province of British Columbia traveled hundreds of kilometers north and east through the mountain passes and blanketed the park.

From the town of Jasper we drove north across the Athabasca River then crossed the Snaring River and drove along the bank of the Athabasca River further northeast to the point where we would walk to the site. It is not marked from the road and since there isn’t a path someone with local knowledge is needed to reach the site by foot. Established as a provisioning depot for the Hudson’s Bay Company, Jasper House operated on this site from around 1830 to 1884 as an important stopover for fur traders who traversed the Athabasca and Yellowhead mountain passes. It was suggested to me that Jasper House is arguably the most significant archaeological site within Jasper National Park. No wonder it has the highest level of protection under Parks Canada’s land use zoning system (Zone 1).

Jasper House National Historic Site is situated on the bank of the Athabasca River just below Jasper Lake. It was designated a National Historic Site in 1926 at which point building depressions, chimney mounds and other structural features could still be seen on the site. The National Historic Site is actually the second Jasper House. The first one, located on Brule Lake to the north-east, was run by Jasper Hawse from 1817 to 1820 and the depot became known as Jasper’s House. The name has stuck and lives on in the name of the current town and the national park that encompasses it. The full reason for its relocation is unknown, but may relate to difficulty in navigating the lake when the water level was low – and the excellent fishing in the surrounding smaller bodies of water. There was also likely a pre-existing network of trails at the new site, where the valley’s of the Snake Indian and Rocky Rivers join the wider Athabasca River. The area around Jasper House could have also provided foraging grounds for the large herds of horses needed for expeditions across the mountains.

Archaeological survey, assessment and excavation were undertaken at Jasper House National Historic Site in the summer of 1984. Conducted by the Archaeological Research Unit of Parks Canada, the investigation aimed to determine the nature and state of preservation of the structural remains and features. Historic records and artistic sketches indicate that the first structures were build around 1830 and that there were likely three permanent log buildings on the site for much of its tenure. However, it seems that the site was partially abandoned by the 1870’s and fully so by 1884.

The archaeological report states:

“The results of the research in 1984 demonstrated that the archaeological record of the Jasper House Site can shed light on the corporate expansion of the Hudson’s Bay Company through the Athabasca River Valley in the 19th Century, Native population dynamics of west-central Alberta and east-central British Columbia in the mid to later 19th Century, and the history of Metis settlement in the region of Jasper National Park.” (Pickard 1985, 53-54)

There is much more to unpack in that statement than is possible in a simple blog post and I will leave it for the interested reader to investigate the social and cultural dynamics of this point in Canadian history for themselves. There is no doubt, however, that the establishment of Jasper House impacted the future of the local landscape and its people.

Pickford, R. (1985). The Site of Jasper House: An Archaeological Assessment (Microfiche Report Series 268). Environment Canada – Parks.

When you walk over the site to day there is frankly not but to see other than slight depressions and mounds where the structures once stood. By using the archaeological report and surrounding mountains as a guide you can identify the layout of the site and visualise what it must have been like 150 years ago. The area is still clear of trees and provides easy access to the water’s edge. It is easy to see why it was an attractive location for a Hudson’s Bay depot or a homestead, and why it remains important to the descendants of those who lived there and those who use(d) the wider area – for instance the indigenous groups whose traditional territories overlap this site.

Before we left we made sure to sign into the guest book that is kept well protected in a small elevated wooden locker. As a tourist the most accessible way to view the site is from the other side of the Athabasca River. From a pull-in off the Yellowhead Hwy you can walk to the edge of the river and look across to the site of Jasper House from an elevated platform. Interpretive signs give visitors an overview of the history of the site and its significance to Jasper National Park and Canada. From this viewpoint it is easy to imagine a small cluster of buildings with smoke rising from the chimney’s and horses being loaded up for a long journey west through the mountain passes.

I recently moved to the Canadian Rocky Mountains and can’t say enough about the wild beauty of the landscape. It felt like home right away. There are so many sites to explore – natural and cultural – from mountain passes and river valleys to historic homesteads and POW camps. The story of this region began many thousands of years ago and continues today.

Some of the Canadian Rocky Mountain range is contained within the national park system. Jasper National Park is the furthest north, with Banff, Yoho, Kootenay, and Glacier to the south. In fact, the Canadian National Parks were born in the Rocky Mountains, with the initial development in 1883 of the Cave and Basin hot springs at the foot of Sulphur Mountain in what is now Banff National Park. The story goes that Canadian Pacific Railway workers William McCardell and Frank McCabe descended into the cave from above and found the hot spring contained within it. The next year they built a small log cabin on the site – intending to capitalize on their ‘discovery’. Others contested their claim and in 1885 the first Prime Minister of Canada, Sir John A. MacDonald, declared the 26 square km (10miles2) around the site as the Banff Hot Springs Reserve. The rest, as they say, is history. Today there are 47 Canadian National Parks (or National Park Reserves) with more proposed.

It is fascinating to me how the beginning of the national parks system is intrinsically tied into the westward push of the railway. So, after hearing the origin story of Canada’s national parks I felt a need to visit Cave and Basin National Historic Site. The location was formally designated a national historic site in 1981, three years before the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Banff National Park is one of the most visited national parks in Canada, and Cave and Basin one of the most visited National Historic Sites. When I arrived in the area I therefore wasn’t surprised by the astounding beauty of the mountains and lakes, or by the volume of visitors walking through the streets of the town of Banff.

We decided to start with a hike along the Sundance Trail to the Sundance Canyon to get a sense of the area. The trailhead is just past the Cave and Basin National Historic Site building complex and the linear hike takes you through the river valley and back to your starting point. It was good to take a step away from the controlled environment of the national historic site and explore the natural landscape surrounding it. When we got to the canyon at the far end of the trail I was delighted to see the first autumn icicles forming on the fallen branches overhanging the rushing water. On the return hike we were rewarded with amazing views of the mountains that encircle the town of Banff and the hot springs.

Returning to the national historic site we entered into full tourist mode. When you enter the site you are greeted by a Parks Canada representative at the front desk who explains the layout and offers some suggestions of what you can see and do inside the complex. We opted to go straight to the cave, stopping first to peruse the interpretive panels that outline the history of the site. The cave is entered by a manufactured tunnel that is very dimly lit. At the end is the natural grotto with the hot spring pool. This is one of the only remaining areas of the site that has not been augmented.

Outside the cave is the restored 1916 swimming pool that is heated by the hot spring. Visitors can no longer swim here – although you can visit the nearby Banff Upper Hot Springs if you want to experience being submerged in the naturally hot mineral water. Also in the Cave and Basin building complex is an interpretive gallery that provides visitors with the history of the national parks system, the Banff area and the hot springs themselves. Outside of this gallery is an open-air area where Interpretive Guides can be found stationed at mock-up railway camp trading tents. Walking along the upper terraces of the buildings you can get a good view of these costumed guides interacting with the visitors.

Also from the upper terrace you can walk up to the top of the cave. From there you can see a recreation of McCardell and McCabe’s log cabin and smell the sulphur emanating from the natural pools. This is also a great vantage point from which to view the surrounding mountains. There is much to explore at the site and we could have spent much more time than we had that day. In fact, when researching for this post I found that there are many day and night-time guided tours of the site that I’d love to try on my next visit. The birthplace of Canada’s national parks certainly did not disappoint.

]]>

In February of last year, during my year of digs, I spent a few weeks in Tasmania with the Flinder’s University Historical Archaeology Field School run by Dr. Heather Burke. We were based at Willow Court, a large complex of buildings that functioned as a mental health institution from 1827 to 2000. The goal for that season’s fieldwork was to prepare the site for excavation by mapping the complex with a total station, doing geophysical surveys to identify sub-soil features and cataloguing artefacts in storage.

While working with the Flinder’s team I was able to spend some time with Dr. Kelsey Lowe surveying the gardens surrounding Frascati House, the cottage that was built by Willow Court’s Superintendent in 1832. We used ground penetrating radar, an electrical resistivity device and a magnetic gradiometer to survey the area in order to target areas to place future excavation trenches. Learning from experts like Dr. Lowe was one of the highlights of my year of digs. I was able to get an insider’s perspective on the pros and cons of doing geophys on historical sites – hidden metal in the ground is not the friend of the archaeological geophysicist!

The second Global Archaeology expert to be featured, Dr. Lowe is an Australian Research Council Senior Research Associate at the University of Southern Queensland who performs geophysical surveys around the world. She conducts fieldwork in the state of Queensland, Australia on Historical Native Mounted Police camps, as well as in Cyprus, Turkey, Southeast Asia and the United States. The landscapes she works in vary from sandstone escarpments in Australia – to limestone formations in Cyprus – to alluvial plains in Southeast Asia. In these vastly different regions of the world she uses the same technology and techniques to understand human behaviour in the built environment.

While Dr. Lowe focuses her energy on archaeological geophysics she has had lots of experience getting her hands dirty in the trenches. Her most memorable archaeological experience was in Cyprus:

“I was assisting a field school in 2015, and as part of the field school, I unearthed a young female burial found on the floor of a Middle Bronze Age mudbrick house during the archaeological excavations. She was adorned with faience beads, copper ingots and spiral earrings. Finding her was completely unexpected as the cemetery for the site was only 50 m away. It was the mudbrick wash from the structure’s walls that preserved her.”

Geophysics is a unique archaeological technique because it is a minimally invasive way to understand the archaeological record. It allows archaeologists to create maps of archaeological features without disturbing them through digging. However, international travel with all that equipment can be a challenge! When doing archaeological prospection Dr. Lowe uses ground-penetrating radar (GPR), magnetometers, electromagnetic induction and resistance meters to map what is below the surface and a total station to map the ground surface itself. After the surveys are done she conducts geoarchaeological analysis in the lab to understand the composition of archaeological soils. These include magnetic susceptibility, loss on ignition, particle size analysis and phosphorus analysis. ESRI ArcGIS is used to process all the data collected and turn it into maps of the archaeological landscapes she walked over days, weeks or months before.

Dr. Lowe’s interdisciplinary background gives her a unique perspective on archaeology. Having starting her archaeological journey with a BA in Anthropology, she has over twelve years of experience in cultural heritage management (CHM) in both the United States and Australia. CHM has given her insights into the management and preservation of heritage sites, as well as an affinity for public outreach and engagement with local archaeology and heritage. Combined with her knowledge of geoarchaeology and near surface geophysics, her fieldwork experience allows her to examine and visualise archaeological landscapes in a unique and insightful way. It is fascinating how two archaeologists can look at the same landscape and see very different things.

When Dr. Lowe was giving the Flinder’s Historical Archaeology fieldschool students, and myself, an introduction to geophysical fieldwork I was struck by how much she knows about her equipment. While my first impression of geophysical survey was that archaeologists get harnessed to a metal box on wheels and pull it through fields, she was able to explain the history and use of each instrument – where it came from, where it has been and what it can reveal to us. I now understand what these tools can allow archaeologists to do. Seeing beneath the surface is something an archaeologist of fifty years ago could never have imagined and it is still and amazing ability.

After spending time with her in Tasmania and more recently interviewing her for this post I was curious to find out what has kept Dr. Lowe so interested in archaeology for over fifteen years:

“There are many aspects of archaeology that attracted me to the job; the first would be having the chance to learn about our (human’s) ancient history. The other part is engaging with local communities or the Indigenous people for whom we are studying, especially their material culture. The last is the chance to travel and work in many places in the world as part of this career and to learn about other areas of the world. I think the community engagement and research outcomes are what keeps me involved in this field.”

*** Thanks so much to Kelsey Lowe for agreeing to be featured as a Global Archaeology Expert and sharing her perspective on archaeology!