For month eleven of Global Archaeology I’ve been in the Anthropology Department of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). I arrived in the midst of a big collection storage move and they needed all hands on deck!

Most of my time was spent on the fourth floor of the Louise Hawley Stone Curatorial Centre in the David Boyle Room, named for Canada’s first full-time professional archaeologist and curator of a ROM precursor, the Ontario Provincial Museum. The curatorial wing of the ROM was opened in 1984 and renamed in 2006 for the late Mrs. Louise Hawley Stone who donated her time and collections to the museum. With her will she created the Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust to help with the upkeep of the curatorial centre and with acquiring new objects for the museum. Without a doubt, the contributions of the ROM’s supporters and historic predecessors have made the museum what it is today.

The ROM has been open for over one hundred years and houses millions of objects, documents and materials. Even with all the expansions it has undergone since it opened in 1914 the museum isn’t big enough to hold all the material in the collections. To help manage the overflow off-site storage facilities were acquired and currently the ROM staff are moving more material there from the museum. Since new material is always coming into and going out of the museum the collection managers constantly re-arrange the collection vaults based on multiple requirements. It’s important to take into account ease of access to objects and documents for ROM staff and visiting researchers. If certain types of material or particular collections are frequently accessed then it is reasonable to keep them on site. Finding the correct place for all the boxes requires a mastery of organisation!

When objects enter a museum they are legally accessioned. Accessioning is when a unique number is given to an object and it is entered into a permanent record such as a database:

Collection managers not only accession the objects, but must also assess and allay immediate environmental demands (relative temperature & humidity), intermittent access and the long-term needs of the collection. Collections are often accepted before the long-term storage is agreed upon, and thus stored temporarily in a staging area. In my travels around the world I’ve learned that such ‘back racks’ of a collections room are a sure spot to find hidden treasures. The bottom shelf of the ‘back rack’ I was helping to catalogue at the ROM held bags of archaeological soil samples, cannon balls and an anchor!

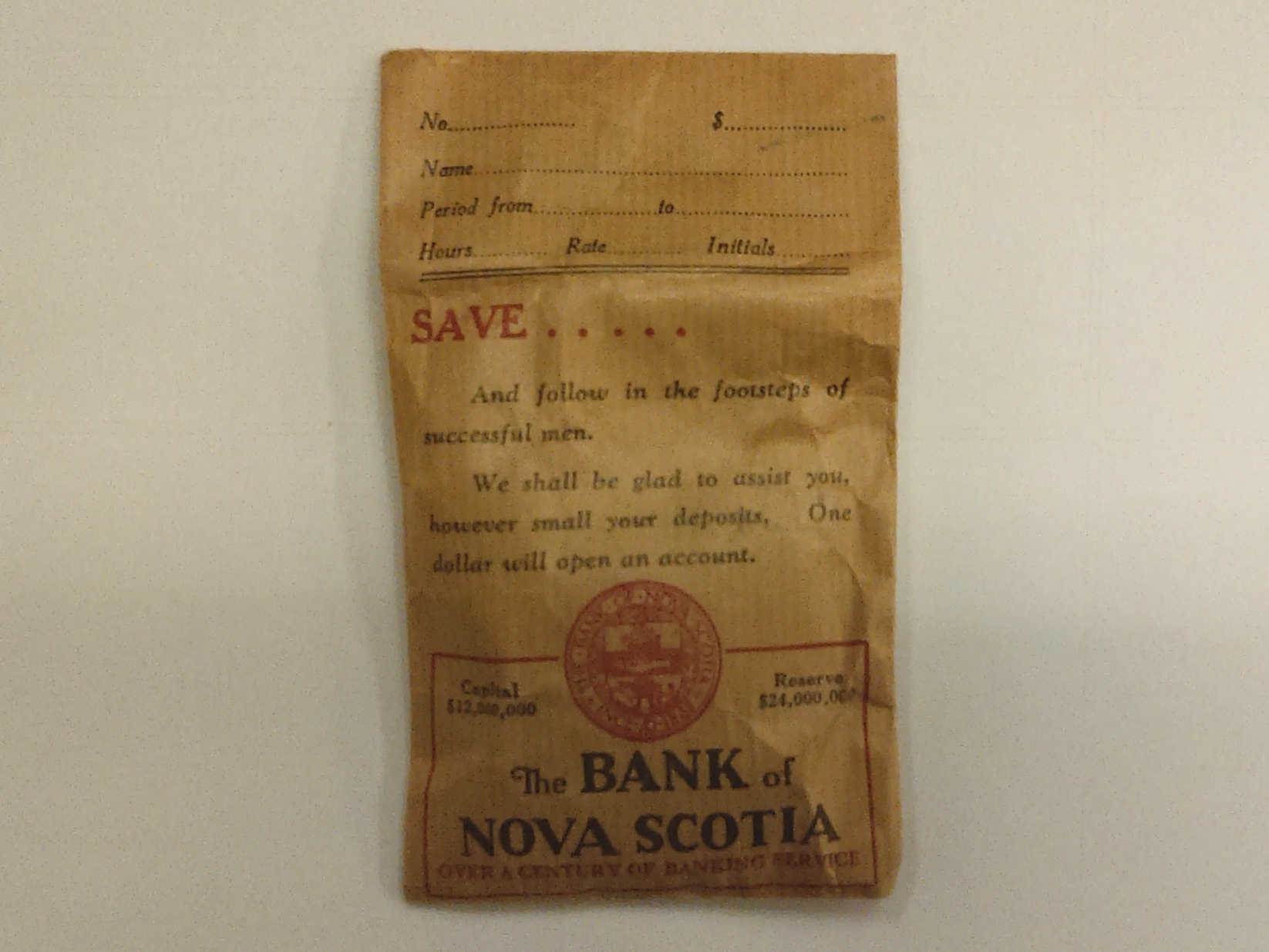

Object moves are a great chance to do some double checking. All the boxes being moved have to be inspected to ensure their labels are correct! Part of the process is to re-record each accessioned object in each box to check against the database. Another aspect of collections moves is ‘rehousing’ objects in better packaging. It is fascinating to see the types of bags and boxes that archaeologists sometimes used in the past! They took advantage of whatever they had on hand in the field: newspapers, matchboxes, cigarette boxes and even bankers bags! One of my tasks at the ROM was to open boxes of excavated material that had been accessioned but not yet re-housed. It is important to remove objects from boxes and/or bags that are ripped or deteriorating to make sure that the archaeological material is protected and not separated from any important information written on its storage container. Today museum professionals use acid free boxes and plastic bags to keep the collections safe from pests and harmful environment factors.

Equally important to ensuring that objects properly leave the collections area is ensuring that any objects entering it go through a certain process to make them safe. The ROM has a large walk-in freezer where all objects and materials coming into the museum from off-site storage areas spend at least 72 hours and in most cases up to 10 days. This is a completely non-toxic and carefully regulated industry process safe for almost all materials. The freezing process works to eliminate pests that could be present in even one tiny object. Every effort has to be made against such a pest infiltrating the rest of the collection. For example, a few of the pests found in any Toronto home could destroy a mummy or feather headdress in a very short time – the risk is too great to cut any corners.

As a lover of objects and puzzles I was more than happy to help the ROM staff sort through boxes. For much of this Global Archaeology year I have been working at the opposite end of the spectrum: excavating the archaeological artefacts and materials that end up in museum collections. I feel very privileged that I have been able to participate in the full archaeological process from start to finish. It’s not something every archaeologist gets the chance to do!