Historic archaeologists can often use written records and maps to identify sites and discover details about people who lived in the past. But equally there are aspects of past lives that were not recorded and can’t be learned from ledgers and letters. Investigations at the abandoned settlement of Kildavie on the Scottish Isle of Mull, run by Heritage and Archaeological Research Practice (HARP), is a perfect example of how physical remains uncovered through archaeology can expand our understanding of historic records.

I joined HARP on the west coast of Scotland at Kildavie in the North West Mull Community Woodland of Langamull for month nine of Global Archaeology. They run an archaeological field school where students help to expand our understanding of the historic abandonment of settlements in Scotland. While there is a grand narrative about the Highland Clearances in this part of the country – with some very real and harrowing accounts to go along with it – the story is not straightforward in every case. While some people were quickly forced out of their homes, other places were more gradually abandoned and Kildavie may be one of these.

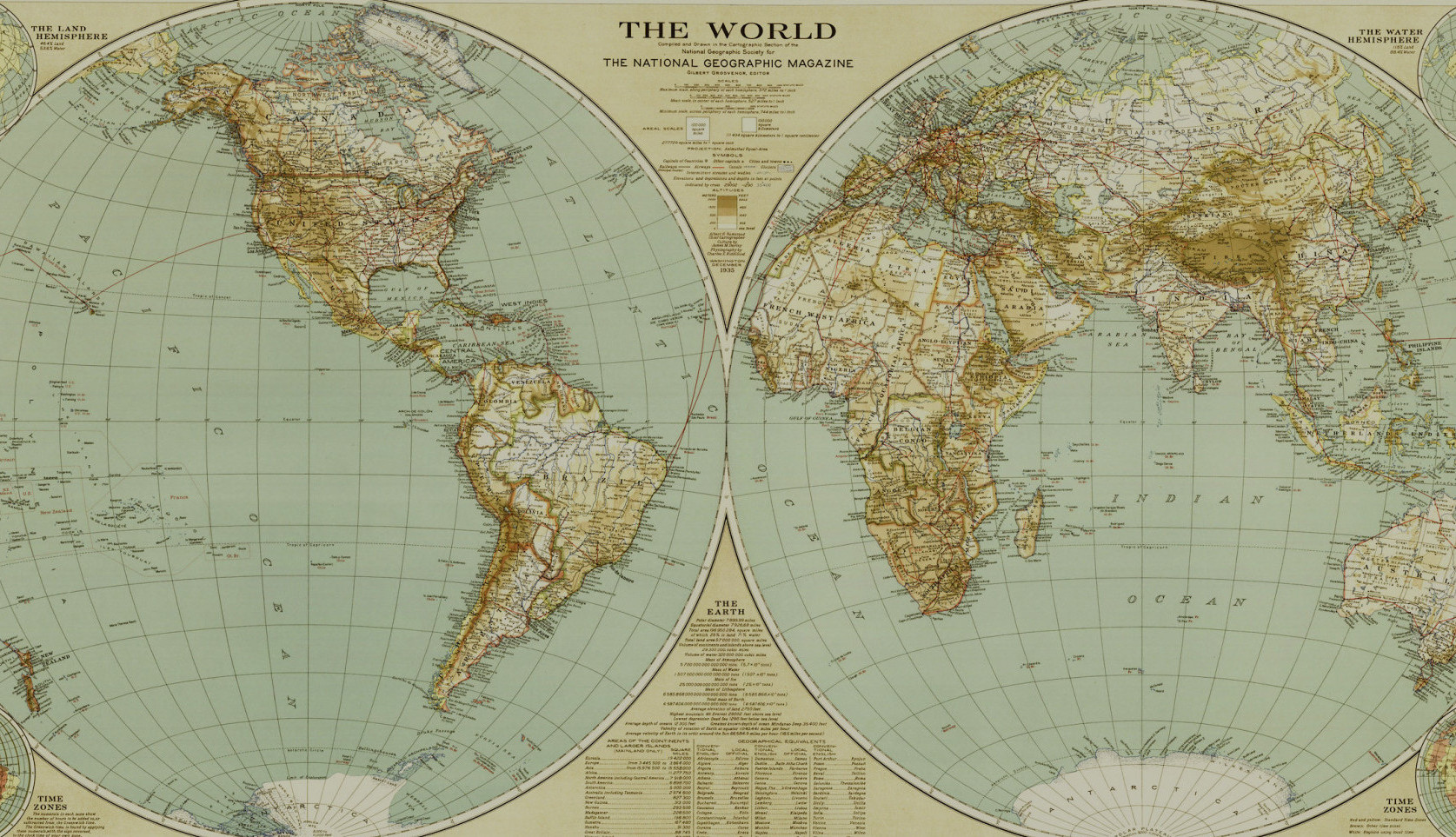

There is archaeological and historic evidence that Kildavie was a domestic settlement in the 17th and 18th centuries until it was abandoned at the beginning of the 19th century. The reason for its final abandonment is unknown, as is the origin of the settlement. Kildavie is depicted on ‘The Island of Mull’ map drawn by Joan Blaeu in 1654 (based on a survey by Timothy Pont in 1575) but the nature of the settlement at this early date is uncertain. On Blaeu’s 1654 map and ‘The Isle of Mull and part of Argyle Shire’ map made by Herman Moll in 1745, Kildavie is marked with a small church and cross. After this date the settlement is only shown as a series of structures. Perhaps there was a church at Kildavie in its earliest days and it became a more domestic settlement later in its life.

As part of the Scotland’s Rural Past project Kildavie was surveyed by the NW Mull Archaeological Interest Group (MAIG) who mapped the general layout of the settlement’s buildings and enclosures which showed that the (approximately sixteen) buildings conform to a general shape and style of construction. Further analysis of the settlement over the past few excavation seasons has highlighted variety between structures that casts uncertainty on how each was used. To discover as much as possible about this variety HARP targeted three areas of the abandoned village for excavation this season: each focused on a different style of structure.

The team is investigating the possibility that one or two of the structures were built for something other than a domestic dwelling, for instance for a cottage industry. It also seems that some buildings were ‘renovated’ and re-used for another purpose. This type of later reuse can be seen in the small dividing walls built in some of the structures, possibly after they went out of use as a home. In 2014 the team revealed a series of ‘cells’ or chambers in a building towards the south of the settlement (Structure 12) that appear to have been added in after its initial construction. There are no doorways into these chambers and so it is likely that they were built when there was no roof on the building and it was being used as a farming structure, possibly for holding sheep.

Above all the archaeological team is hoping that the excavations at Kildavie and the objects uncovered will provide more information about the lives of those who lived there. In the historic records there is no complete description of the number of people living in the settlement and what their occupations were. By excavating as wide a variety of structures as possible the team hopes to identify differences in dates of occupation and use of the structures. If one structure contains only pottery and other objects from the 16th century and another structure only contains material dated to the 18th century it can be suggested that these two structures were used centuries apart, even if they are in the same settlement and constructed in a similar way.

There is more work to be done at Kildavie and HARP will be returning in 2017 to continue excavating the trenches begun this season and opening some new ones. If you are interested in getting involved have a look at the HARP website where there is more information about the Kildavie project and the others they run in Scotland and Cyprus. Equally, if you wanted to visit the site as a holiday maker Kildavie is now easy to reach due to the hard work of MAIG who have cleared the area, set up signage and constructed walking paths through the glen with the support of Archaeology Scotland’s Adopt-a-Monument scheme.